Disrespect in health care: An epistemic injustice

In this issue of the Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, Entwistle and colleagues address an urgent concern in our health care systems, namely that patients are sometimes treated with disrespect and that this disrespect is not sufficiently considered or addressed. They outline a number of important reasons for this deficit, including that respect is fundamentally misunderstood and that it can be difficult to measure. I suggest these difficulties result from hermeneutical injustice, a form of epistemic injustice wherein important social phenomena are obscured from collective understanding, owing to the persistent marginalisation of certain groups of people, in this case, the socially disadvantaged groups who are most at risk of being disrespected.

Epistemic injustice in bioethics

For nearly half a century, the ethical education of health professionals has been dominated by Beauchamp and Childress’s Principles of Biomedical Ethics.3 The principles – respect for autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice – emerged from The Belmont Report4 and described a set of considerations originally intended to guide biomedical research rather than clinical care. At that time, the paternalistic culture of health care had gained public attention and the ethical principle that had the most profound impact was ‘respect for autonomy’.

The principle of ‘respect for autonomy’ has (in some editions) also been referred to as ‘respect for persons’, yet discussions of respect within Beauchamp and Childress’s conceptualisation focus exclusively on autonomy regardless of what it is called. Interpretations of our obligation to respect patients according to Beauchamp and Childress are thus limited to activities such as informed consent and noninterference with patient decisions, and. Furthermore, that limited obligation is not owed to all equally. According to the most recent 2019 edition, ‘Obligations to respect autonomy do not extend to persons who … are immature, incapacitated, ignorant, coerced, exploited, or the like. Infants, irrationally suicidal individuals, and drug-dependent patients are examples’. With this same single-minded focus on autonomy, Ruth Macklin, past president of the International Association of Bioethics, wrote, ‘Dignity is a useless concept – it means no more than respect for persons or their autonomy’.

These views, abstracted from Kantian philosophy, are harmful to efforts to promote respect in health care. Most people do not believe that dignity is a useless concept, and the narrow focus on autonomy has, as Entwistle and colleagues rightly point out, undermined our ability to identify other morally problematic behaviours. Our own work exploring public perspectives about respect has revealed several important themes; these include recognition of the unconditional value (dignity) of each person; treating patients as equals; listening to patients and not dismissing their concerns; knowing patients as individuals; being polite; and responding to suffering. Participants in our studies described many instances of disrespect, quite similar to the experiences highlighted by Entwistle et al. Examples are being treated like trash, not treated as a person, treated rudely or ignored, not having their concerns listened to or taken seriously, being stereotyped, talked down to, etc. Indeed, in all of these studies, there was not a single participant who responded that they thought dignity was unimportant. Yet these voices that come directly from people who have experienced disrespect and that provide a robust and empirical understanding of what it means to respect patients as persons have been hermeneutically marginalised and thus have not had the opportunity to shape collective understanding.

Despite these shortcomings in conceptualising respect, the history of bioethics’ impact on health care leaves room for hope that a more holistic view of respect can change health care culture and improve the care patients receive. Health care was paternalistic, and bioethics played an important role in revolutionising it. I have not met a doctor or nurse that does not at least understand, if not embrace, that respecting patient autonomy is a core ethical principle. Social justice is a central concern for bioethicists, and disrespect – embodied as the failure to see each and every person as equally valuable – is a core element of social injustice. Bioethics can catalyse another revolution, one where we embrace the idea that each person has equal and unconditional moral worth, and where we can more inclusively and thoroughly outline all its implications, as Entwistle and colleagues have done, and as the previously marginalised public has begun to. Perhaps someday we can say that we have not met a health professional who does not understand, if not embrace, that disrespect – the failure to relate to others as equals – is of moral importance.

Full article here:

Beach MC. Disrespect in health care: An epistemic injustice. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy. 2023;29(1):1-2. doi:10.1177/13558196231212851

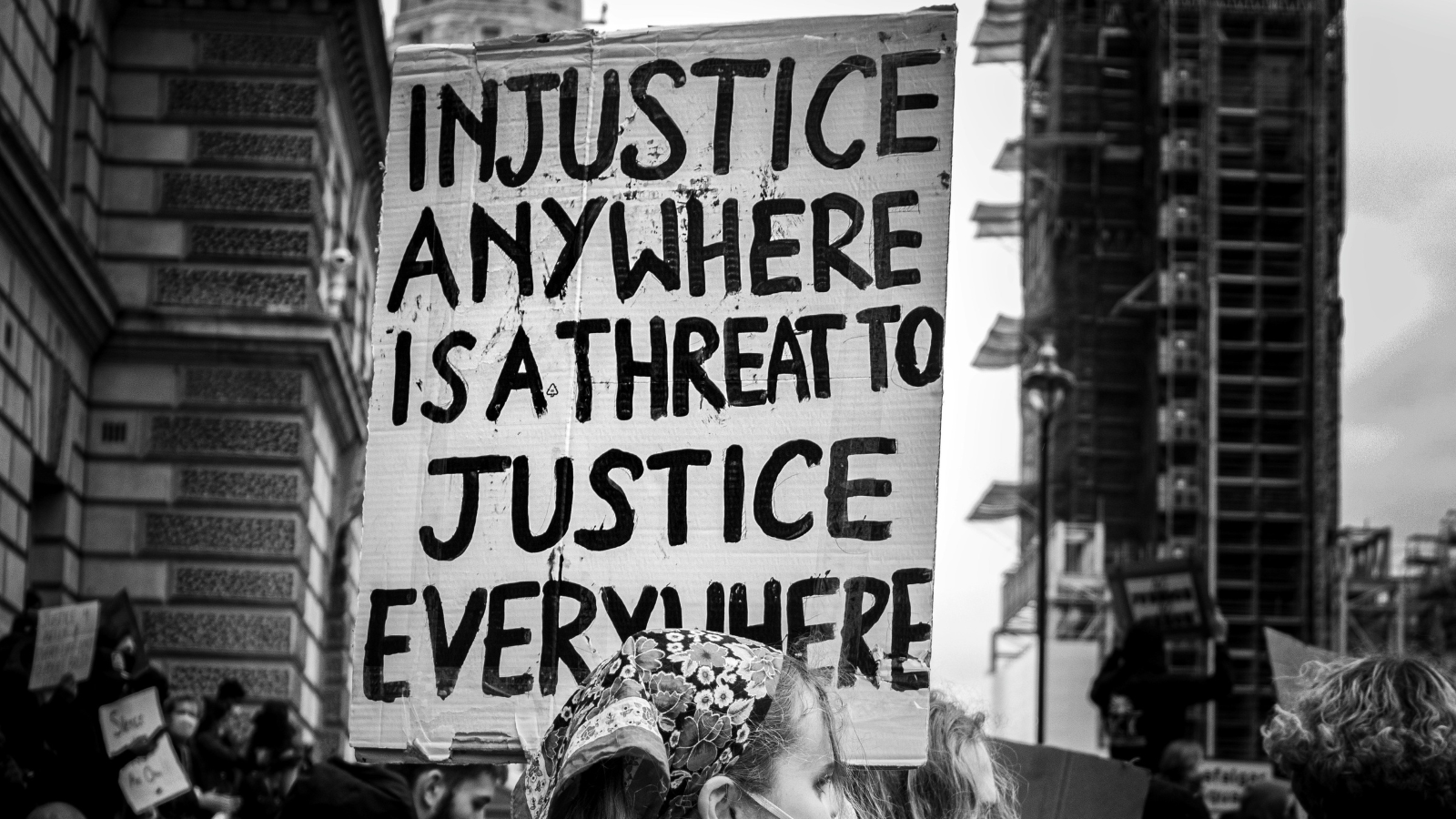

Photo by Jack Skinner on Unsplash